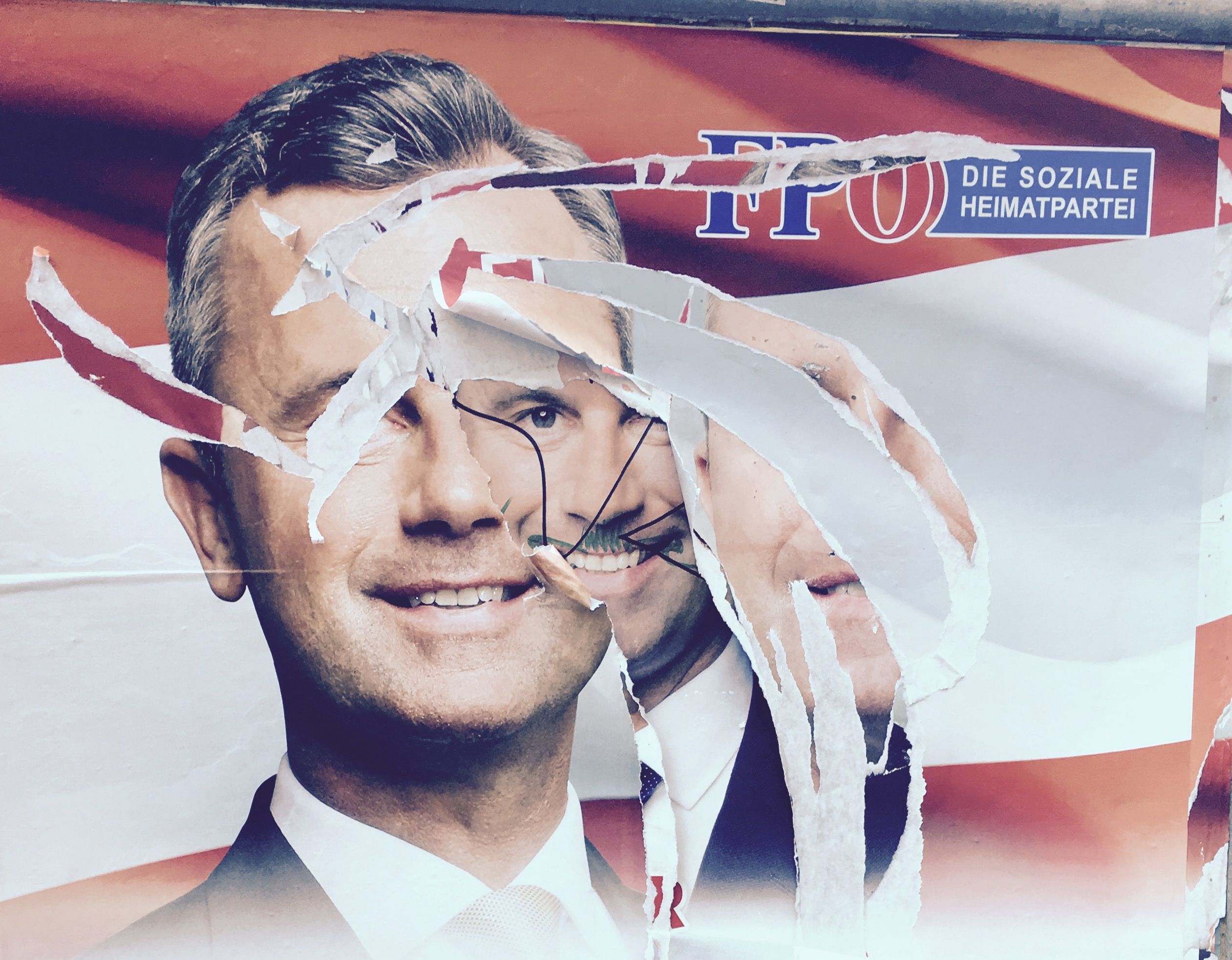

The election of the Green candidate Alexander Van der Bellen as president of Austria in the second round of the presidential elections on 23 May caused a sigh of relief across Europe. But while the election of an extreme right-wing president seemed to be prevented his extremely narrow defeat – by only 30.000 votes – was a reason for concern rather than celebration. A candidate of the extreme right, Norbert Hofer of Austria’s Freedom Party (FPÖ), won 49,7% of the votes in the presidential election of a European country: this scenario was almost unthinkable only a few years ago.

As if things weren’t bad enough already, on 1 July the results of the second round of voting were annulled by the Austrian Constitutional Court and the second round between Van der Bellen and Hofer will be repeated on 2 October. According to the latest polls, Norbert Hofer will be the winner. The Austrian nightmare continues, but little attention has been paid to this crucial fight during the last months. Understandably so due to the British EU referendum, the sheer endless Spanish post-election farce or the terror attacks in Nice. Still, we must not ignore the likelyhood that in just a month’s time Austrians will elect an extreme right-wing candidate as their president.

This scenario will not affect only Austria. It will be of great symbolic importance for the whole of Europe, as it will defy the strong conviction that many politicians, activists and theorists maintain· namely that an extreme right-wing candidate cannot win in a second round of elections. We are heading towards the moment when we will no longer speak about the electoral rise but about the electoral victory of the extreme Right. The possibility that an extreme right-wing politicianis directly elected as head of state in a European democracy must alert us and put into question our reassuring beliefs concerning the political reflexes of the European electoral bodies. An extreme right-wing candidate can win elections in Europe, even the presidential elections. We must acknowledge that. This scenario is no longer a far-fetched but a very real possibility and a very frightening one if we take into account that in 2017 the French presidential election will take place.

According to many polls, Marine Le Pen will win the first round of the French presidential election. So, we have to ask ourselves, is it still unthinkable, is it impossible for Marine Le Pen to win the second round of the presidential elections? Is there anything to reassure us that an extreme right-wing candidate cannot win the election in France?

France has been in a permanent state of emergency since the Paris attacks in November 2015. Even if the declaration of a state of emergency was a necessary and justifiable act at that moment, it can be said that its extension to the present day constitutes a significant blow to the democratic rights of the population. This summer a swimsuit, the so called burkini, became the object that symbolised how the extreme right-wing discourse about Muslims, Islam and terrorism became both mainstream and institutional. Cannes and around 20 other French municipalities banned the burkini. At least in one case armed policemen forced a woman to remove her clothing on a beach. The mayor of Cannes explicitly connected the burkini with Islamic extremism. Nicolas Sarkozy, who will be again candidate for the French presidency, is in favour of a nationwide ban on burkinis and he stated that ‘I will be the president that re-establishes the authority of the state (…) I want to be the president who guarantees the safety of France and of every French person (…) I refuse to let the burkini impose itself in French beaches and swimming pools, there must be a law to ban it throughout the republic’s territory.’ The discussion here of course is not about the burkini as such. It symbolises the whole debate around migration, multicultural societies and integration that combined with the actual incidents of Islamic terrorism has triggered fear all across Europe. If we permit this discourse to become mainstream, we should not be surprised when voters will choose a genuine representative of the extreme Right in order to translate this discourse into practice.

The fight against extreme right-wing ideas cannot be limited to the fight against the well known and openly extreme right-wing parties. These ideas have found many supporters in the centre-right parties and unfortunately even in some centre-left parties. Let us not forget that the party of Viktor Orbán is a member of the European People’s Party and the party of Robert Fico, the Slovak Prime Minister, belongs to the Party of European Socialists.

The diffusion of extreme right-wing ideas in the political scene and in societies and the establishing of an ‘Extreme Centre’ create the fertile ground that can potentially lead to the electoral win of an extreme right-wing party. So, we must fight against specific parties but most importantly we must combat specific ideas across the political spectrum, wherever we find them. The political struggle is essentially a struggle about ideas, a struggle about hegemony, as the Italian theorist Antonio Gramsci has taught us. This is a struggle that my generation should not lose. There is no margin for defeat. Democracy, in its essence, is in great danger.

You can download the article in PDF here.

Antonis Galanopoulos (1989) is from Greece and holds a bachelor’s degree in Psychology and a Master’s degree in Political Theory and Philosophy.