The Brexit vote reflects a triumph for nativist political ideas that have long been espoused by radicals and extremists. Yet it would be unfair and indeed, completely absurd to argue that the 52% of Leave voters are extremists or even radicals. The vote to leave the EU has provided succour to right-wing populists across the European Union as well as Republican Presidential Candidate Donald Trump. However, many who voted Leave would be appalled by the politics of the Front National or Trump. The magnitude and complexity of the June vote begs the question: how do we even begin to understand Brexit beyond the confines of electoral data?

The Brexit vote has led to numerous questions over its long, medium and short-term causes – the latter to be poured over in no less than three books by Westminster-based journalists to be published over the coming months focusing entirely on the Vote Leave and Leave.EU campaigns. One argument I plan to make in my own book (to be published in 2017 by Melville House), which focuses on the origins of Brexit, relates to both the historical and recent political atmosphere within Britain (and indeed Europe). The backdrop of the vote to leave the EU was that of a political environment which has become, since the turn of the 21st century, one in which anti-immigrant sentiment, xenophobia and criticism of multiculturalism and so-called ‘liberal elites’ have become increasingly mainstream. Regular proponents of such views – the far-right – whilst being little more than a political irritant and electoral irrelevance for much of their history have nevertheless had many of their views vindicated by politicians and the press. This suggests we need to reappraise our understanding of far-right ‘success’.

Aristotle Kallis has argued that far-right electoral breakthroughs are often overstated. This has certainly been the case in the UK where moral panic over alleged far/radical right electoral insurgencies has been common. The extremist British National Party, whilst achieving a brief period of electoral success between 2003 and 2009, never really threatened to break through. Even the radical right-wing UKIP, undoubtedly the more successful of the two, has achieved very little electoral success beyond second-order local and European election victories. Yet, as Kallis argues, far-right parties ‘have been notably more successful in translating their poll ratings into (disproportionately stronger) political and socio-cultural influence’ [1].

Kallis describes this ‘mainstreaming’ as the:

(partial or full) endorsement by political agents of the so-called political ‘mainstream’, and/or by broader sectors of society, of ‘extreme’ (in some cases even taboo) ideas and attitudes without necessarily leading to tangible association […] with the extremist parties that advocate them most vociferously.

Noting that the notion of mainstreaming radically changes our perceptions of extreme and radical right ‘success’, Kallis goes on to argue that:

this development has the potential to unleash previously unthinkable levels of social demand for some extreme ideas that were originally considered taboo but which have, in the process, become, allegedly, more legitimised and more acceptable to a wider audience [2].

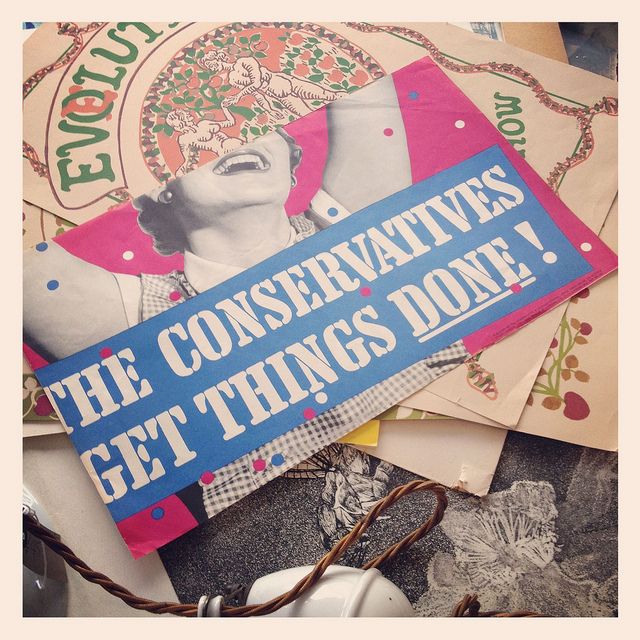

We need look no further for an example of what far-right mainstreaming looks like than the Conservative Party Autumn Conference, hosted in the beginning of October in Birmingham. Theresa May, who despite campaigning (apathetically) for Remain, was ushered in as Prime Minister following Brexit and David Cameron’s resignation, announced at this occasion that a so-called ‘hard Brexit’ would be pursued – meaning that Britain would leave both the EU and European Single Market. This is in spite of the significant economic uncertainty and a grave risk to British jobs dependent on EU trade. Subsequently, the pound sunk to a 31-year low. Why would May allow the country to shoot itself in the foot economically by going for hard Brexit? Freedom of movement is a concession that May is unwilling to make to ensure Britain’s continued unencumbered trade with the EU.

Whilst May also announced that there would a gradual phasing-out of foreign doctors by 2026, new Home Secretary, Amber Rudd (who campaigned vigorously for Remain), yesterday announced a raft of new restrictions to ‘prevent migrants taking the jobs British people can do’. These attempts to radically curb immigration include restrictions on foreign students and skilled workers. Rudd also pledged to force companies to ‘list’ foreign employees and to ‘name and shame’ companies who hire foreign workers. Perhaps the most insidious set of statements from the conference came from Liam Fox, Secretary for International Trade, who sinisterly criticised immigrants who come to the UK and ‘consume’ the nation’s wealth. In addition, Fox refused to guarantee the status of EU nationals living in Britain, describing them as one of Britain’s ‘main cards’ held by Theresa May enabling her to negotiate favourable terms for Britain’s EU exit. The implication, whilst an inconceivable one, but one Fox nevertheless refuses to deny, is that he is perfectly prepared to see nearly three million people deported should Britain not get what it wants in its negotiations to leave the EU.

The far-right has always been an electoral disaster in Britain, leading many to dismiss them as an irrelevance. Yet, we are currently witnessing a steady victory for xenophobes, nationalists and extremists, as the British Government steals their ideas and apes their rhetoric. In her first conference speech as Prime Minister, Theresa May stated in an attack on so-called ‘liberal elites’: ‘If you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere’. Not only does this sound like a sanitised quote one would normally hear from the far-right, it signals the direction in which British politics is currently travelling at breakneck speed.

You can download the article in PDF here.

[1] A. Kallis, „Breaking Taboos and “Mainstreaming the Extreme”: The Debates on Restricting Islamic Symbols in Contemporary Europe‟ in R. Wodak, M. Khosravinik & B. Mral (eds.) Right-Wing Populism in Europe (London; New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), p.57.

[2] A. Kallis, „Breaking Taboos and “Mainstreaming the Extreme”: The Debates on Restricting Islamic Symbols in Contemporary Europe‟ in R. Wodak, M. Khosravinik & B. Mral (eds.) Right-Wing Populism in Europe (London; New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), p.57.

Paul Stocker (1989) is from the UK and is currently completing a PhD in History, researching the British far-right.