My name is Armanda. I am 25 years old and a student of Economics at the University of Bologna, Italy.

On 11 July, the European Summit on Youth Unemployment should have taken place in Turin. Offically, the Italian government headed by Renzi has judged it more appropriate to postpone the meeting to the end of the Italian council presidency, making certain reservations about the place, which now probably will be Brussels.

As a matter of fact, the upcoming summit had stimulated immediately the constitution of a network, #ribaltiamoilvertice, whose aim was to overturn the discussion, in order to highlight the failures of recent employment strategies. Given the high probability of massive protests during the summit, the need of postponing the meeting has also been interpreted as an attempt to avoid moments of conflicts.

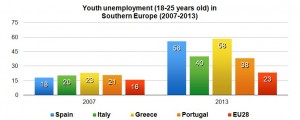

Indeed, data about current unemployment are dramatic: from 2007 to now, the rate of youth unemployment has more than doubled in Greece, Spain and Italy and almost doubled in Portugal. Moreover in last the years, the living conditions of young people have been deteriorating including cultural services and education. The highest percentage of early leavers from education and training is recorded in the same countries which have a high rate of youth unemployment, an increasing number of NEET and a low level of tertiary educational attainment (1) (especially Italy and Portugal).

The EU being focused on the consolidation of the fiscal budget and on the reduction of public debt of the countries mentioned above, has not done enough to solve this socio-economic emergency.

The Youth Guarantee Programme has been implemented only in a scarce number of countries and Greece and Portugal are not among them; moreover where the programme is adopted, it is weakened by the important level of discretion conceded to the Member States.

When the youth employment initiative was launched in February 2013, only a small amount of resources was provided (6 billion for the period 2014-2010). Now countries are asked to invest directly in these programmes, even if at the same time they are also asked to be even stricter in the management of public resources.

However, this contradiction is only apparent, since it actually reflects clearly the priorities of the EU and youth unemployment is probably off the list, in spite of continuing proclamations to the contrary.

In order to deal with this issue, it would be necessary to adopt an expansive policy, to foster the recovery of southern countries together with a new regulation of the labour market which should facilitate long term contracts, cancel job insecurity and guarantee workers’ rights and quality of jobs. However, such an ambitious process of structural change is far from the policy agenda of the two major parliamentary groups, which are going to elect a new President of the European Commission in line with the current economic and political choices. In the meanwhile, youth unemployment is still there, with or without the summit.

Footnotes

(1) The share of the population aged 30-34 years who have successfully completed university or university-like (tertiary-level) education is 22,4 % in Italy and 29,2 % in Portugal, higher in Greece 34,6% and 40,7% in Spain, 36,8% for EU28.