My name is Armanda. I am 25 years old and a student of Economics at the University of Bologna, Italy.

In November 2014, Eurojust has published the Official Report on the Strategic Project on Environmental Crime with the aim of analysing the current situation and the difficulties that national authorities face to prosecute the increasing diffusion of environmental criminal activities. However, the report has not raised an adequate level of attention and consciousness, even though it deals with a topic that regards us as civil society as well as our health. Indeed, the Project was launched precisely out of the observation of the paradoxical absence of really informative statistics on the impact of this type of crime, in spite of the increase of its cross border dimension. The study focuses on three criminal areas: traffic in endangered species, illegal traffic in waste and surface water pollution. Information has been collected through direct analysis of specific cases, questionnaires sent to national authorities in close collaboration with IMPEL and ENPE.

Particularly interesting and serious is the problem of illegal traffic in waste. As underlined in the text, with the economic crisis there has been a huge increase in the number of companies trying to avoid to pay tax on waste, to reduce transport costs and to circumvent legislation on it. Moreover, there is a strong connection between illegal traffic of waste and the growth of the global trade towards Africa and India, which hides the traffic of materials extracted from electronic waste that has a dramatic impact on the environment. On the other side, within Europe this traffic has assumed a significant and structured dimension, unfortunately underestimated and still addressed in a partial and ineffective way.

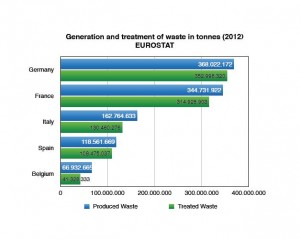

Toxic Europe, an excellent and award-winning Italian documentary of 2011, tries to explain how globalised and well organised the system of management of illegal waste is. It shows, for example, that the people and organisations placed at the head of the national Italian illegal management of waste have extended their power throughout Europe, as in the case of Glina in Romania, where the biggest European landfill is located. Here a complex mix of illegal traffic of waste, money laundering between members of Cosa Nostra and the Romanian branch of Ecorec, responsible for the management of waste in Glina, has been discovered. One easy way of getting an idea of the dimension of this system is, as suggested in the documentary by the public magistrate Raffaele Cantone, to consider the difference between the total amount of waste produced and the total amount of waste treated. The difference should be zero, but it is higher than zero in almost all countries. We reported in the table some data from 2012, but consider that we are actually referring to millions of tons disappeared and that this is still an underestimation of all the ‘ghost waste’ which is produced, not registered and then treated in an illegal way.

Clearly, “cross border cooperation and mutual legal assistance” is essential and the procedure of getting the required information on the origin of waste and on the companies involved can be very complex and long, often leading often to ineffective control and supervision. Furthermore, not only cooperation is missing and there are not yet “well established contact points” among countries, but also the environmental legislation presents a high level of technicality about the categories and component of waste and the adequate expertise is not developed across European Union. To further complicate the situation, the implementation and the interpretation of European legislative law at national level is not harmonised and presents significant differences. As a result, not only the level of investigation but also the adoption of necessary measures of punishments “by effective, proportionate and dissuasive criminal penalties“ remains just vaguely defined under each national interpretation.

This insufficient level of coordination, control and implementation of law, represents a potential and concrete source of high profit for criminal organisations which are actually exploiting on the one side the scarce level of monitoring concerning traffic waste and on the other side the rising demand from companies willing to reduce the costs of transport and waste disposal From the tapped conversation between two mafia criminals in Italy, one sentence sums it all up: “It enters as waste, it comes out as gold”. Indeed, interests of different transnational criminal organisations around Europe are making profit, destroying the environment and endangering people’s health, especially of whose living near to the landfills where toxic products are buried in secret. In a time of lacking cooperation in and of disillusionment about Europe, a United Toxic Illegal Europe has evolved which we should oppose with stronger coordination, legal efficacy and continuous control.